There are dozens of books and hundreds of online articles that explain what mind mapping is and how to do it. So many, in fact, that there hardly seems to be room for another one.

All of these explanations follow the same path. First, the question “What is mind mapping?” is interpreted as “What is a mind map?” Then there is an explanation of what a mind map is, some examples, and advice on how to create a mind map from a blank page. The advice ranges from basic suggestions to strict formulas. Most of the advice is similar, but some of it is conflicting.

But what if this is the wrong question? Knowing what mind mapping is might not explain why you should invest valuable time in it. A more interesting and useful question is: “What is it like to be good at mind mapping?” This is hardly ever asked or answered, so we will try to answer it.

What is it like to be “good” at mind mapping?

We first need to be clear about what mind mapping is. Then we can look at what successful mind mapping is. We will focus on mind mapping software, and not on mind maps as popularized by Tony Buzan.

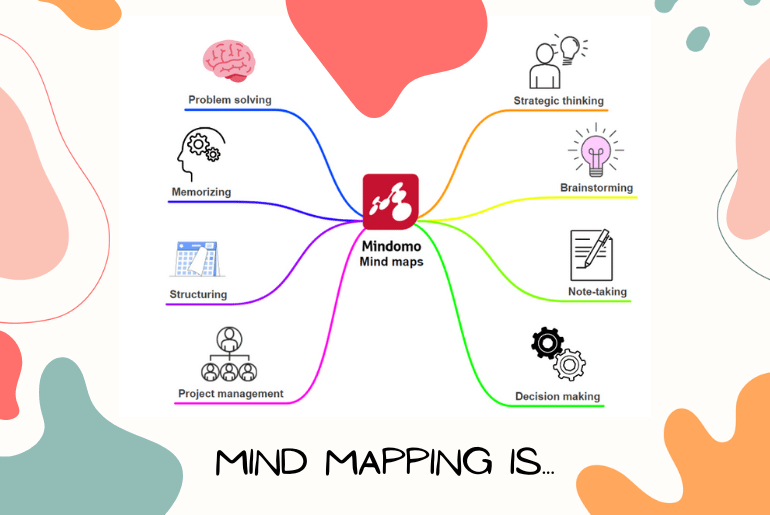

Most definitions of a mind map tell us that it is a hierarchical diagram around a central concept, with connected information radiating outwards. Single word topics and short phrases make it easier to read. Images and color make it memorable and visually appealing. Mind mapping can be used by anyone for almost any purpose. Popular uses are brainstorming, studying, planning, writing, problem solving, time management, and organizing information. Research showing the benefits of mind mapping to exam grades is often quoted.

This explanation leads towards the idea that mind mapping is about making good mind maps, and a good mind map is one that follows the rules, such as having a strong central image. Tony Buzan established “mind mapping championships” where the best mind maps are judged.

The criteria include keeping to the mind mapping rules. The judges also decide how accurate the maps are and how well (in their estimation) the author has understood the subject. This is done by looking at the map, not by interviewing its author. However, the software is not allowed, so this approach doesn’t shed much light on the best ways to use mind mapping software.

If you have ever browsed through some of the thousands of mind maps available in online galleries, you may have noticed that there is a very wide range of maps. Some are small, some large, some clearly incomplete, some are easy to read, and some are obscure. Some have single word topics, and some have whole paragraphs. Some have a central image, and some don’t. Some look pretty, some are ugly, and some just seem a bit strange. One of the articles explaining mind mapping shows a dozen examples. It is striking that there are more differences than similarities between these examples. The only common feature shared by all mind maps is that they are hierarchical and radiate outwards from the center of the page. Beyond that, almost anything goes.

This leads us to wonder whether it is helpful to judge a mind map on its own and whether looking at examples of other people’s mind maps actually tells us anything.

A mind map is only one frame from a movie

Drawing mind maps is a creative exercise involving imagination, inspiration, recall, insight, problem solving, and making connections. We can’t separate mind maps from their authors. The map is a snapshot of a dynamic process, not the goal of that process.

Our brains contain billions of mirror neurons, which fire when we do something and also when we see someone else doing the same thing. When we are engaged in watching an activity, we imagine we are doing it and what it feels like. When we watch a video of someone falling off their skateboard and landing on a handrail, we feel their pain. A still photograph of the same event doesn’t trigger the same anticipation and empathy.

A mind map is a still photograph of a dynamic process of discovery and building. The map doesn’t tell us much about the changes that are taking place in the author’s mind. We don’t travel on the same journey as the author just by looking at their map. You can’t tell from a snapshot whether it has been through five iterations or five hundred. The “aha!” moments and the sudden flood of understanding are not captured in a static image.

Modern technology has given us the ability to see what is beneath paintings. Until now, we could see only what the artist intended us to see. But we can now look below the surface to find a different sketch underneath and understand what has been added and taken away. This causes much excitement and interest. It turns out that we are just as interested in the story behind the painting as we are in the final result. It brings the painting to life and shows that the artist is a real person that we can connect with.

Leonardo da Vinci did not wake up one morning and paint the Mona Lisa in one sitting. He made sketches, tried different versions, and made changes. The backstory is part of the painting, yet the final image does not capture it. Knowing what someone else knows is useful. Understanding why and how they came to know it is much more revealing. We learn something from the journey, not just from the destination.

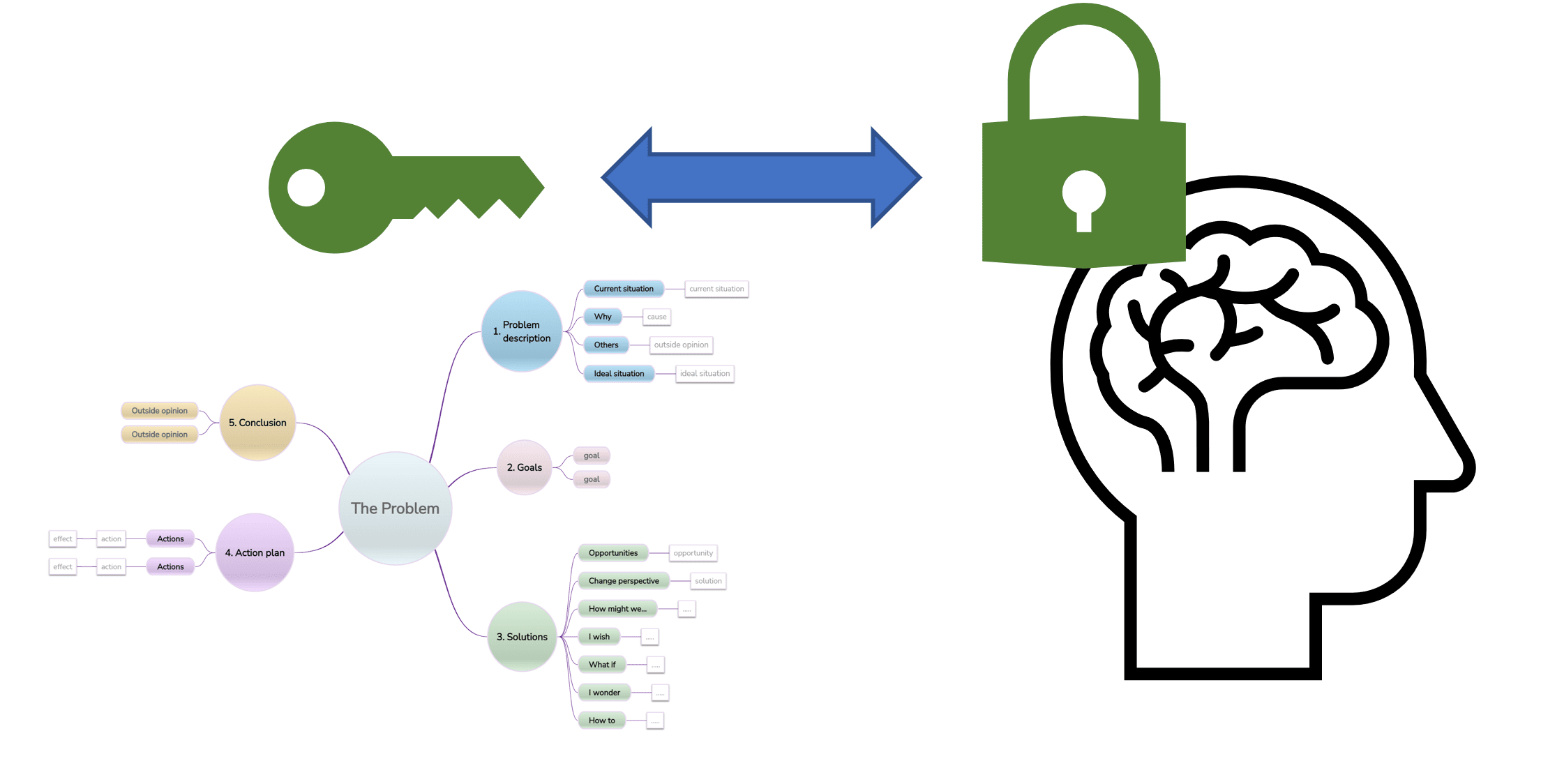

A mind map is a key to the author’s mind

The relationship between the author and their mind map can be likened to a lock and key. A lock is no use unless you have a key. A key is no use on its own without a lock. A shiny key on a colored ribbon on it might look great, but not work very well. A plain and dull key might unlock a treasure chest full of jewels at a single turn. You can’t really tell how well it works by looking at the key alone.

Mind mapping frequently unlocks what you already know, making it usable and actionable. Mind mapping is a conversation that follows interesting threads and brings out points that had been hidden from view. If you weren’t part of the conversation, the mind map by itself gives only fleeting clues.

To the right person, a single word is enough to unlock an idea. You have a key but are left to imagine what kind of lock it might fit. It’s hard to tell whether a map works well from the map alone.

Writing is a tool for thinking

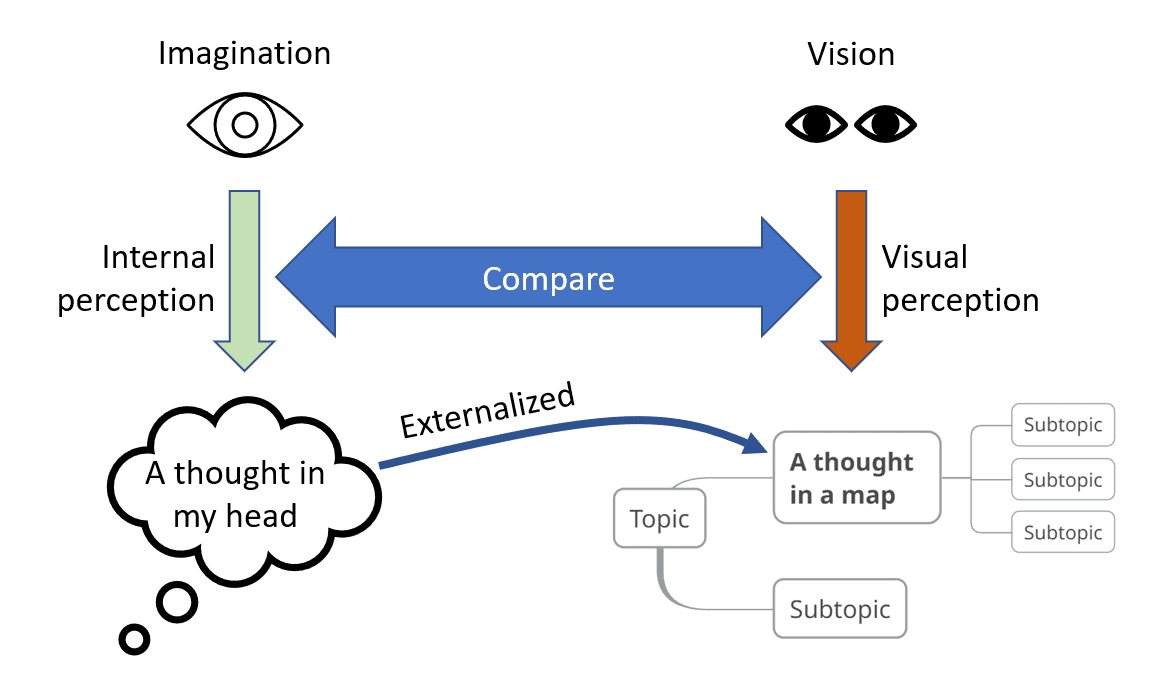

Writing is a tool for thinking. Externalizing your thoughts and ideas is essential for you to master them. Not copying word for word, not highlighting phrases in books, not making margin notes, but rewriting things in your own words. There is a lot of research showing the link between writing and memory, critical thinking, creativity, and more. Externalizing an idea or piece of information means we don’t have to “keep it in mind” for the moment. Our working memory is very limited, and writing things down makes space for new thoughts.

We can only learn new things by connecting them to what we already know. When we have made a connection, we can refine it. Knowledge is contained in the relationships between pieces of information, not in the bare facts themselves.

Just about any type of diagram works to create a scaffolding for thinking. A diagram in which words are connected by lines is easy to draw. A line always means continuity, commonality, or connection. We have cells in our visual system whose only job is to recognize lines and draw our attention to them.

A tree or spider diagram has a very simple layout yet is easy to extend. You can start with a blank page and keep adding sub-branches, almost without limit. We are good at breaking things down into smaller pieces to find out what makes them tick. Mind mapping software that can automatically make space when we want to insert something new means we can concentrate on the ideas and let the software take care of the layout for us.

As well as being easy to extend, hierarchies also create patterns. We usually assume that all the items on a list have something in common. If you can see a pattern in three things, then finding a fourth or fifth is not just an easy step to take but can be hard to resist.

Putting these things together, a mind map is just a diagram that

- is written in your own words,

- makes connections between ideas,

- is easy to expand, and

- helps you to see patterns.

These properties make it perfectly suited for creating a wide range of scaffolding for thinking, understanding, learning, and planning.

Plan for change

The steps recommended in most of the “how to” articles will help you to draw a picture that looks like a mind map. But making it valuable and meaningful is not something that comes from a formula. It can only come from the interaction between you and your map. Learning to create a mind map is only a stepping stone to a deeper skill – learning how to learn and create meaning from information.

Creating a mind map with software is not about starting at the central concept and working outwards in a logical, ordered fashion. It’s about the gradual evolution of a structure that looks like you did that. You have to make a start somewhere, and it doesn’t really matter where. As you build up your map and your insight deepens you change the structure, so that new information and new ideas can be seamlessly absorbed.

A good design is able to handle change without drama. The ability to handle change is more important in the long term than performance today. Ask any project manager about inevitable change. A mind map that can easily be restructured and extended is much more valuable than one that is correct today but too difficult to modify tomorrow. A mind map reaches the end of its useful life when it is easier to start again than to make the changes that it really needs.

As mentioned above, we can only learn new things by connecting them to something we already know. Whether you are making a map of an existing issue, something new that you want to learn, or something that doesn’t exist yet, your starting point is always something you already know. From there, you are trying to find a “shape” for the subject that makes it easy to add new information and generate ideas. Adding new things to a map should strengthen it, not weaken it.

When starting with a blank page, nothing belongs anywhere yet. You can make a guess at the “basic ordering ideas”, but you must be prepared to change these as your map grows. In physics, the “observer effect” says it is impossible to perfectly measure anything, because the act of measuring something changes it. With mind maps, adding anything to a map changes it. Sometimes, the impact spreads out far beyond the new fragment, changing the meaning of existing topics. This is a good thing. Any opportunity to shift your perspective will lead to new thinking and new insights.

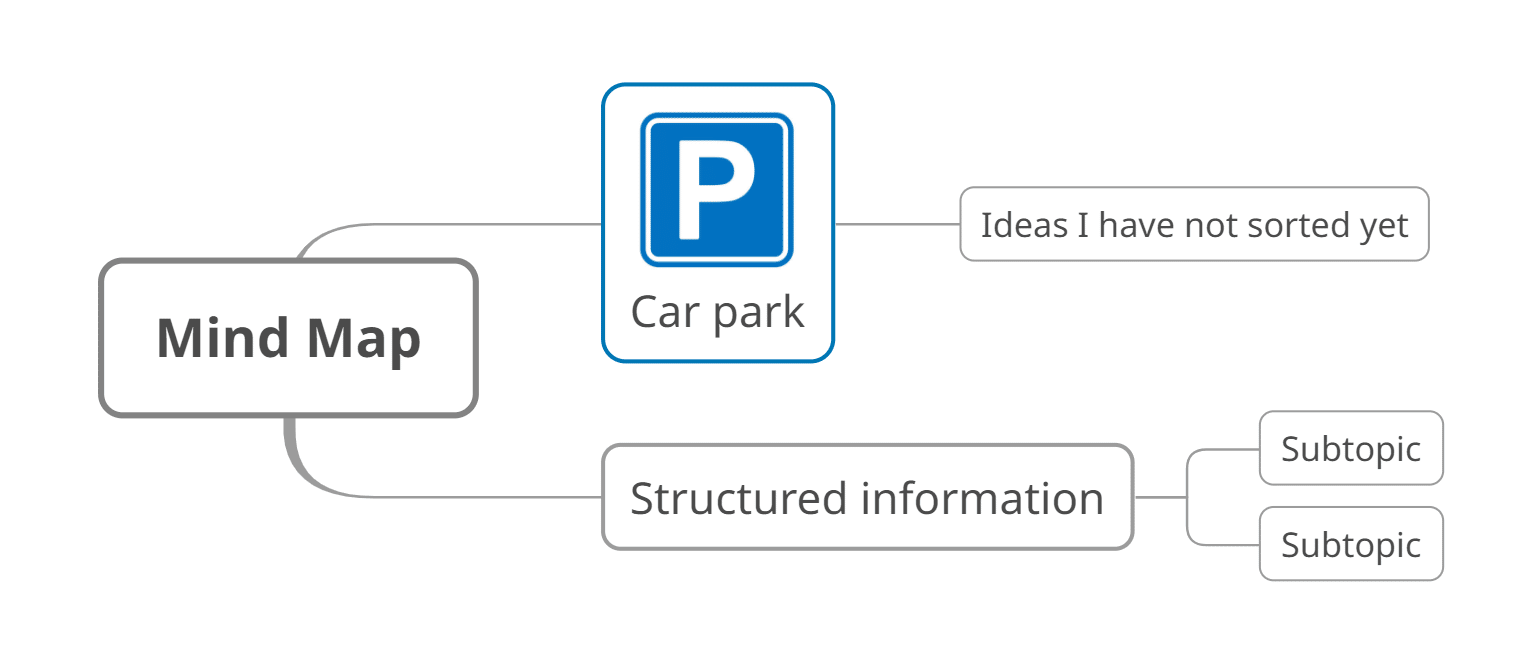

Start with a “car park” topic

One technique is to start every map with a “Car park” topic. This is where you park things before you have worked out where they really belong. When a new bit of information arrives or an idea comes to you, it goes in the car park first.

From the car park tree, you can:

- Discard a topic if it is not relevant to your objectives.

- Move a topic to the best place on your map. It should reinforce existing knowledge, fit a pattern, fill a gap, and be a sensible place to look when you need to find it again.

- Develop a new destination for a topic.

- Conclude that this piece of information or idea is relevant and important, but the map must be reorganized to integrate it meaningfully.

If you know deep down that your map needs to be reorganized, you must be prepared to do that sooner rather than later. Temporarily putting something in the “wrong” place because you don’t have the time to reorganize will lead to trouble in the future. Everyone has maps where some important concept got buried four levels down because that’s just where it surfaced and it never got fixed. These are the maps that you avoid returning to. You are better leaving something in the car park than moving it to an obscure place where it disrupts the flow.

Get immediate feedback from your mind map

Feedback is essential to progress. Without feedback, we can believe that our ideas and knowledge need no improvement. Only if we are willing to seek and understand feedback can we move forwards.

Your mind map gives you immediate feedback on your thinking. When you think about something, you see it in your “mind’s eye” or imagination. When you write it down and look at it, you see it with your eyes. You are now seeing things in stereo, from two different positions. Do they look the same? Does the map represent what you actually meant? Does it really fit where you have placed it? By committing something to the map, you are testing your thinking. When creating maps, it is normal to rephrase things and move them around several times until the structure starts to solidify. You should expect to move things around quite a lot in the early stages of building a map.

Wrap-up

Instead of trying to define what a “good” mind map is, we can list desirable qualities in terms of what a good map enables you to do.

A “good” mind map means:

- If asked, you could briefly state why you had made this map and what it enables you to do.

- You feel confident about explaining the subject to others, using your map as a guide. Thinking about teaching others is a good way to clarify the important points and the thinking behind them.

- You can reorganize your map if you need to. It is not so delicate or complicated that you are afraid to try.

- You can find things in the map and feel confident that if you can’t find them, they are not there.

- The number of times you feel the need to reorganize your map is reducing and you feel increasingly confident about integrating new ideas and information.

- You have a way of dealing with fragments of information or new ideas that seem relevant, but don’t fit into the map. These are opportunities to strengthen it.

- Leaving a partially completed map alone for a while leads to new ideas and new understanding when you return to it. This is especially useful for problem solving situations.

- You feel confident about returning to this map in a year’s time when you have forgotten most of the detail. It will help you to grasp the basics again and continue to use it. This probably means avoiding single word topics in favor of statements.

Being good at mind mapping means creating maps that can always be updated and improved. A good mind map is does not need to have a nice central image, one word per line or plenty of color. Instead, it should be a snapshot of a flexible and thoughtful process that always strives for better.

Keep it smart, simple, and creative!

Author: Nick Duffill